When I started this blog, I went looking for people who had tried this kind of retrospective writing in other media, and I was very happy to discover Club Soderbergh. Hosted by Carla Donnelly along with Maggie and Jessie Scott, the podcast went through his films in more or less chronological order, researching deeply and bringing a delightful fizz of differing perspectives to the work. The creators even had to extend its run to account for Soderbergh’s unretirement. Though they have not caught up to his work since 2020, I hope they will pick up their microphones again in the very different world we now inhabit.

Donnelly has instead, along with cohost Philip Thiel, resumed work on her earlier podcast Across the Aisle. Together, the two review exhibitions, film screenings, and theater in Melbourne and Geelong.1Their preferred spelling might be Djilang? I’m sorry if I’m mistaken, I’ve only heard them use the word aloud! I’ve never been to Australia, but I’ve enjoyed listening to the two of them discuss plays I haven’t seen and art I can only imagine; I enjoy the parasocial pull of a warm rapport between clever friends, and I already know that at least one of them has some taste in common with me.

In Episode 51, during a discussion of an underwhelming gallery show at the ACMI museum, Thiel delicately termed the presentation a “chamber work.” That phrase lodged itself in my mind. I knew the concept of chamber music, but I’m not a musician, and only after that framing did I come to think of the format as one that describes itself in terms of constraint. When you write and play a composition intended for performance in small spaces, by small groups, you are shaping the result by means of a powerful set of boundaries that has continued to produce new variations for centuries.

I am not rash enough to make any predictions about the future of the film industry, particularly after this year’s historic moment of Hollywood labor solidarity, but I think there are already plenty of examples of the way targeting a movie for a home audience shapes that work too. Kimi (2022) is the third of three movies Soderbergh directed explicitly for2(The Service Formerly Known As) HBO Max under a deal signed in early 2020. All three sit an emerging space that lends the production style of twentieth-century TV movies some of the prestige branding once only accorded to theatrical release.

Kimi’s screenwriter, David Koepp, called it a “bottle movie” for its focus on a contained location. I think describing it as a chamber work is equally appropriate, even if it did have at least one day of shooting that involved a thousand extras.3To me, it seems clear that the courageous bystanders among those extras are responding as if her kidnappers are DHS agents or other federal police. That would be an explicit reference to extrajudicial detainment of protesters in 2020 Portland. But my perspective is that of someone who lived in Portland for a long time, and I wonder if those incidents left the same impression on other people! Its instrumentation and its players are deliberately limited, with the goal of producing work for the small screen.

“There’s a very, very small, well-defined perimeter that the story exists within… and [Koepp] likes to take that restriction and just go as deep into it and explore as many possibilities [as] he can come up with. And I like those too… It’s a challenge, but I think when you’re forced to think laterally, instead of vertically–so that whenever you’re trying to address a problem you’re not going to that place of, ‘well, we just need more money, it just needs to be bigger.’”

Soderbergh on The Film Comment Podcast, helpfully restating this site’s thesis

Kimi (2022) is a story about one small person, Zoë Kravitz’s Angela, staying dogged in pursuing a truth against the violence that capitalists can deploy when their plans are interrupted. It’s also a story about agoraphobia in the age of plague: the first and third acts are set entirely within the walls of a one-bedroom condo.4Albeit, I have to say, a pretty large condo for one person by current Seattle standards.

As always, I’m not going to summarize the movie’s plot, but I am going to spoil many parts of it. It’s still available to watch on MAX—for now5Sip from a sun-warmed trash bin, David Zaslav!—and you can get a sense of its outline from Benjamin Lee’s review in the Guardian or Elizabeth Pagano’s at One37pm.

Lee’s review has a nice nod to one of the film’s clear antecedents, The Net (1996),6Not a great film—I’m still not sure what the maguffin virus actually did?—but I will always be fond of it for teenage Brendan/Sandra Bullock reasons. a thriller about another woman named Angela isolated and estranged by the digital tools of her livelihood. Soderbergh did not hesitate, as usual, to name more of the movies that populated his mood board of influences for this one. That’s how you end up with articles like “Steven Soderbergh Says ‘Kimi’ Is A Cross Between ‘The Conversation,’ ‘Rear Window’ & ‘Panic Room’” spun out of fifty seconds of podcast time.7The Conversation (1974) in particular always makes it into Soderbergh’s list of his favorite movies; his primary web domain references a recurring piece of nonsense from it.

But let’s go back to that quote about a “small, well-defined perimeter.” The film breaks its own bottle for Angela’s frantic, fear-driven excursions into the outer world, including that scene with the thousand extras. That break doesn’t negate the constraint of its setting, because it’s a tool to use, not a rule to cling to. Reaching for other tools too just clarifies how much shape the primary tool lends the work. In a similar vein, I think that when the filmmakers start listing off all these citations, they’re not saying it’s a “cross between” anything. They’re talking about how interwoven references help expand the film’s text beyond the tight boundary of a minor work.

Soderbergh has always been a referential director. He loves watching and talking about movies too much to be anything else. Here, as with King of the Hill (1993), he likes to invert his riffs, putting Angela on the far end of the voyeur’s lens, and making her house key a thing that keeps her in as much as it keeps the world out.

Music composers and producers deal in references too: distorting samples to create hooks and beats, or quoting a phrase from one song into another to build a harmony.8Zoë Kravitz’s father, you may know, is a musician who has been criticized for excessive quotation, but I like his music so those critics can go suck rocks. At its best, the act of taking a piece from an unexpected source and mixing it into something new can elevate both works. And to that point, I don’t think the films of David Fincher and Frances Ford Coppola are the only references to be found in Kimi (2022). Those references also include John Hughes and Chris Columbus.

There is another well-known movie, after all, about an isolated young person with sensory-sensitivity issues, a standoffish affect, and very strong lifestyle preferences. When his home is invaded by a tall man and a short man who wish him grievous harm, he too resorts to quick thinking and improvised weaponry to defend it with lethal force.

His name, as one might recall from this startling grace note?

I’m hardly the only one to have drawn this connection, but I don’t think I would have put it together myself if not for the casting of Devin Ratray, who people of my age cohort may remember from the same film as Buzz.

Many reviews of Kimi (2022) refer to it as “spare,” “stripped-down,” or “economical,” and at 90 minutes and a tight budget, none of those adjectives are unfair.9I had a note here that its production budget was $3.5 million, which is the figure listed on the film’s Wikipedia article. But I can’t find an actual source for that number—citation needed!—and now suspect it was extracted in error from this Seattle Times article about state-level film rebates. To return to the sampling analogy, those aren’t words that are typically used to describe reference-heavy music. But I can think of one band who made maybe the most sample-rich album ever and who also created their most influential song out of spare, stripped-down, economical pieces. That song is the one that plays over Angela’s cathartic fight scene at the climax of the film.

“Sabotage” was born out of strict constraints itself, designed from inception to build suspense with its abrupt pattern of stops. I read about its origin in a booklet half my life ago, and it has always stuck with me. To repeat the obvious, I’m not a musician, but it felt so cool to glimpse the rules around the song’s edges, granting me some understanding of why a piece of music I love works the way it does. It was one of the first times I started puzzling over how strong constraints are intertwined with striking art.

The framing for this entire blog came from my listening to a 2017 interview Soderbergh gave to John Nugent at Empire Magazine, wherein the director mentioned offhand that before starting a movie, he always asks himself what rules he can use to separate it from the rest of his body of work. He also tossed out this working guideline about his use of music in his films.

“I’m always on the lookout for an opportunity to have the score not do what the scenes are doing. And sort of use it as a way to… to turn it into a third thing, as opposed to, like, doubling down on the emotion of the scene itself. I always ask myself that question… what if I go in the other direction? For instance, if I have a sequence with a series of fast cuts in it, what if I have a piece of slow music under it? You know… you have to make sure you’re not always falling into this trap of having everything doing the same thing.”

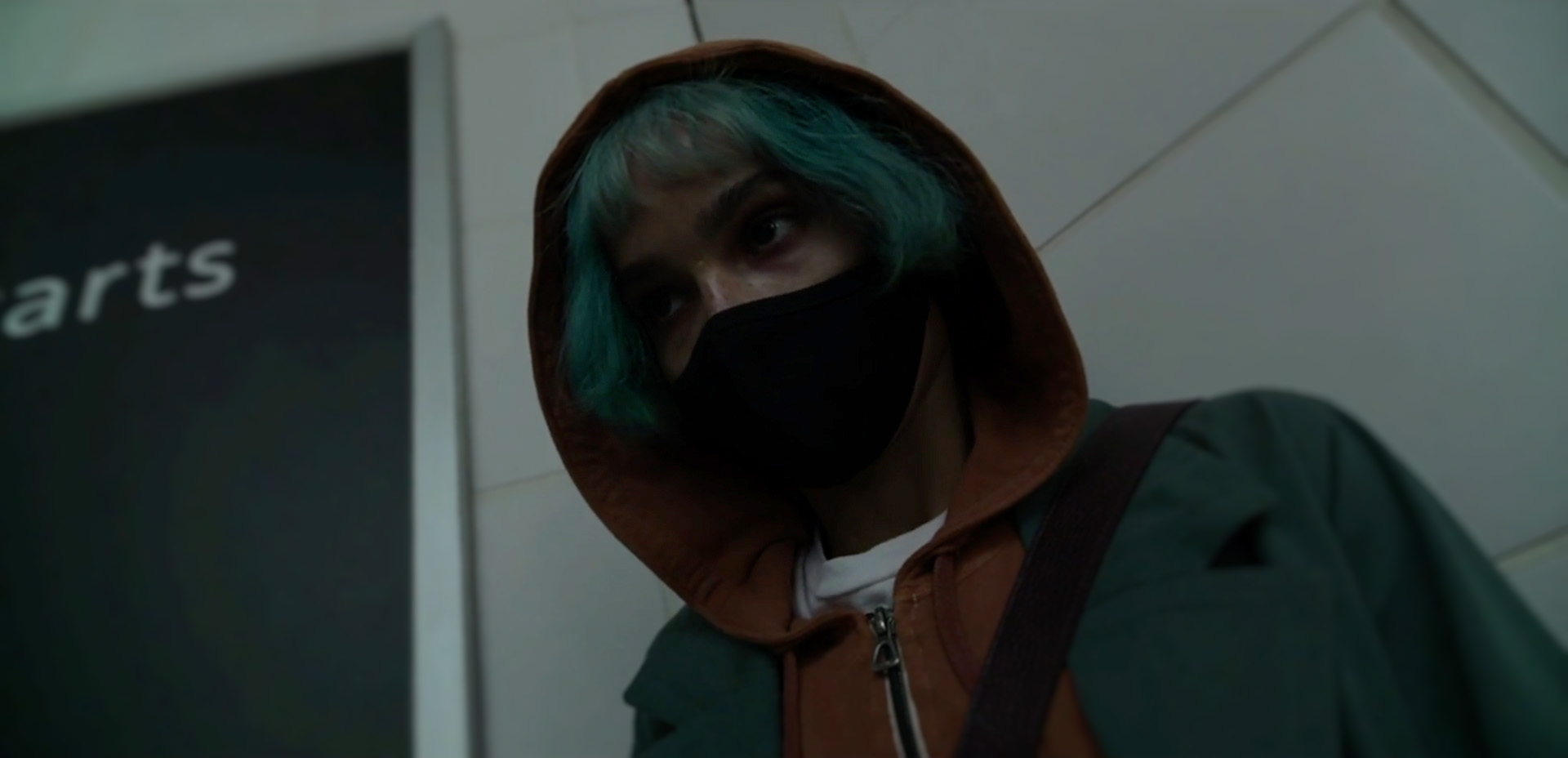

Kimi (2022) makes use of this exact principle throughout its second act, which opens with Angela braving the world outside her apartment; she’s pursued at first by the unseen demons of her own emotional history, and soon thereafter by actual forces summoned to harm her. The jittery, undercranked camera heightens tension in a way that recalls a zombie movie. Angela’s mask and hood, by costume designer Helen Mirojnick, cover the distinctive shock of blue hair that Kravitz herself chose, as if she’s put on armor against perception. Along with Kravitz’s expressive physical work, they suggest a warrior prepared for a stealth mission.

But the dreamy music is such a clear contrast that it heightens these scenes to the haunting and hallucinatory. It’s Cliff Martinez again, still working with Soderbergh 33 years after sex, lies, and videotape (1989). Soderbergh asked Martinez for something different from the brass-heavy scores of the films like The Parallax View (1974), The Conversation (1974), and Panic Room (2002) that he discussed with Koepp.

“I said, look, I really wanna be in that Bernard Herrmann space. But there has to be some aspect to it that doesn’t just make it feel like a copy. … These kinds of films are very score-dependent, so… it’s yours to lose, in the sense that if you don’t have a great score, that’s an unforced error that’s going to hurt the film.”

Soderbergh, to Devika Girish and Clinton Krute, on the aforementioned Film Comment podcast

Bernard Herrmann is one of the great film composers of the twentieth century, and had an extraordinary run of work with Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, and Orson Welles. This is the man who wrote the violin sting for Psycho (1960), so I wouldn’t necessarily have associated him with hushed reverie. But he’s also the man whose film score debut was the overture for Citizen Kane (1941). If you add that ominous undertone to, say, the fairyland-twinkling parts of Beethoven’s “Appassionata”—which appears diegetically in Kimi (2022) —then you start to get something like what Martinez produced.

What would the film have been like if you scored it with standard-issue music—say, David Sardy’s track from the bike chase in Premium Rush (2012)?

It doesn’t work at all the same way. I think Soderbergh is right: being less thoughtful here would have robbed the movie of its best moments. Now, this isn’t to bag on the writer-director of Premium Rush (2012), the very same David Koepp who wrote Kimi (2022), except that’s a lie, it is to bag on him, because I have consistently disliked his work for decades.

If I were a more honest writer I would have come right out and said this at the beginning. One reason I told you last time I was going to discuss “one I don’t actually like” was because I knew this was the first time Soderbergh and Koepp had worked together.10Nonetheless, while I didn’t fully take to the movie last year, watching it over and over to sift out all these words has made me feel fond of it! That does keep happening. Soderbergh interests me because he’s made so many movies and yet so rarely lets me down; Koepp, who is also prolific, always finds a way to disappoint me. Buy me a drink sometime and I’ll go on about this for half an hour, but that’s not the point of this post.

One thing I could hold Koepp to account for, though, is that this movie seems like it should highlight the dangerous surveillance apparatus built into every smart speaker, but it… doesn’t? Kimi, the device, is effectively a hero in Kimi (2022), the film: murder victim Samantha manages to get the truth about her death out through a voice memo, and Angela’s clever use of voice commands at the film’s end gives her an edge over her assailants. Amygdala, the company making Kimi and employing Angela, clearly has a creepy file on our protagonist that includes her medical records and biometrics—but there’s never an indication that such things were caught by her speaker. They’re just a part of her getting a job with a tech startup in the hell of 21st-century American employment.

Kimi (2022) is a movie about people’s relationships with technology, and how the COVID pandemic changed those relationships. I mean the word “technology” in the sense defined by Ursula Franklin, here: the mindset, approaches, and habits humans build up with their tools, not just the tools themselves. Technology is both Angela’s hand sanitizer and her habit of waving her hands in vertical parallel to dry them. Technology is thousands of Kimi machines passively listening all the time, and technology is the queue of snippets they decontextualize and send back for Angela’s data-labeling work.11The size and luxury of her condo are extra jarring when one knows how little labelers get paid. Technology isn’t just the fact that villainous Amygdala CEO Bradley Hasling, played by Derek DelGaudio, uses a ring light for his Zoom interview at the film’s opening; it’s also the fact that he puts bookshelves in his garage and keeps his pajama pants on for it.

My own relationship with pants has certainly changed since 2020. I’d suspect Steven Soderbergh’s did too, at least for a while. His career demonstrates how quickly he’s adjusted to new tools as they become available: centering his breakout feature around a consumer video camera, writing screenplays on a Mac II in the early 90s, risking a massive financial undertaking on prototype RED cameras for Che (2004), and shooting Unsane (2018) and High Flying Bird (2019) on an iPhone 8.

But even as a habitual early adopter, Soderbergh is not averse to criticizing the tech he uses. He stopped making movies with phones, even as their cameras improved, because Apple ignored him when he wrote to ask why he couldn’t lock the exposure for a given shot. And if you watched his new series Command Z, which he hosted and streamed on his own website, you’ll get a sense of just how intensely he must feel about the architects of the tipping point we all straddle in 2023.

This is what I’ve come to appreciate about Kimi (2022): the anger it contains isn’t directed at regular people who rely on Alexa or Siri, or even the laborers who keep their services running. It’s directed at the financial technology we call the startup, the way the money and expectations inherent to that technology distort people’s reality, and the force multipliers used to harm and kill the human beings who inconvenience investment capital.

When listing off all those filmic references in interviews, Soderbergh spoke admiringly of David Fincher and Panic Room (2002), another David Koepp screenplay. But twenty years later, some of its moral foundations seem fragile. For one thing, the heroes of that story own a four-story brownstone in Manhattan paid for by the pharmaceutical industry, while Forest Whitaker’s criminal antagonist just wants enough money to retain custody of his kids. The film grants Whitaker’s character a measure of sympathy, but it’s not ambiguous about who is rewarded and who is punished in the end.

I think Koepp’s second use of the home-under-construction bottle set for Kimi (2022) is an improvement, and shows a more modern political awareness. Credit to him, too, for anticipating how the work of data labeling might rise to prominence, when he wrote the script years before the launch of ChatGPT.

But at the same time, I have to debit both Koepp and Soderbergh for this film’s failure of an ending. The constraint of the three-act screenplay demands a resolution that shows how the protagonist has changed through the events depicted, and Angela’s story makes it clear that her isolation is untenable for her physical and emotional health. But after spending so much of its runtime showing how much trauma the protagonist carries, and how her neurodivergence affects her relationships to people and the outside world, the film offers a pretty jarring final freeze-frame. All it took for Angela to walk out happily into sunshine again was being forced to shoot her torturers point-blank in their skulls with a nail gun? Really? Killing another human being made her feel better instead of worse?

I believe that cathartic action can help lead to profound change in survivors of many kinds, and there’s plenty of precedent for this kind of denouement in movie history. But it still came across to me as if the filmmakers had embraced the Two Bonks On The Head Cures Amnesia theory of mental illness. Even a chamber piece should carry its central theme through the last note.

I hope that at some point I’ll get to bother Carla Donnelly for some insights about a Soderbergh movie. (If Carla is reading this: hi, Carla!) I have a much fainter hope that production designer Philip Messina might search the internet for his own name and come across this article, and then email me, because of all the crew members involved in Kimi (2022), he’s the one I would be most interested to talk to. I’m so curious to learn how the actual Kimi unit was conceived. Its anodyne matte cowling, uniform perforated speaker grille, and rippling LEDs all nail the school of Dieter Rams knockoff industrial design that most high-profile electronics have reached for in the last decade. There are other, subtler technologies he selected, too—such as Angela’s deadbolt, a seemingly innocuous prop that nonetheless requires a key to be inserted from inside to unlock the outside world. And I’d love to know how the decision to cast Soderbergh’s ex-wife Betsy Brantley as Kimi’s voice came about!

I might have jinxed myself last time by announcing what film I was going to write about next, so this time I’m going to… not do that. But rest assured I’m still puttering away here in Chicago, kind reader. And I hope that by the time I post my next retrospective, tech unions will still be growing, and that the concessions the Hollywood guilds have won against algorithmic absorption this year are only previews of stories still to come.

- 1Their preferred spelling might be Djilang? I’m sorry if I’m mistaken, I’ve only heard them use the word aloud!

- 2(The Service Formerly Known As)

- 3To me, it seems clear that the courageous bystanders among those extras are responding as if her kidnappers are DHS agents or other federal police. That would be an explicit reference to extrajudicial detainment of protesters in 2020 Portland. But my perspective is that of someone who lived in Portland for a long time, and I wonder if those incidents left the same impression on other people!

- 4Albeit, I have to say, a pretty large condo for one person by current Seattle standards.

- 5Sip from a sun-warmed trash bin, David Zaslav!

- 6Not a great film—I’m still not sure what the maguffin virus actually did?—but I will always be fond of it for teenage Brendan/Sandra Bullock reasons.

- 7The Conversation (1974) in particular always makes it into Soderbergh’s list of his favorite movies; his primary web domain references a recurring piece of nonsense from it.

- 8Zoë Kravitz’s father, you may know, is a musician who has been criticized for excessive quotation, but I like his music so those critics can go suck rocks.

- 9I had a note here that its production budget was $3.5 million, which is the figure listed on the film’s Wikipedia article. But I can’t find an actual source for that number—citation needed!—and now suspect it was extracted in error from this Seattle Times article about state-level film rebates.

- 10Nonetheless, while I didn’t fully take to the movie last year, watching it over and over to sift out all these words has made me feel fond of it! That does keep happening.

- 11The size and luxury of her condo are extra jarring when one knows how little labelers get paid.

0 Comments

1 Pingback