I don’t think I would say Steven Soderbergh is my favorite all-time director,1Rian Johnson. Sorry. nor is he the director of my favorite movie.2Hackers (1995). He’s not even the director of my favorite Magic Mike movie.3As if there’s any doubt. But there’s something about his work that has compelled me for a long time, ever since I wandered into Out of Sight (1998) at the Cinemark Movies 8 in Richmond, Kentucky.

Despite his intermittent claims to retire, Soderbergh has produced a lot over his career, and as of this writing I’ve watched less than a third of his feature films—to say nothing of his concert film, television series, interactive media, scripts he wrote for other people, and books. My goal for this blog is to get through as much of that material as I can, and write about it. So if he’s not my favorite, then why?

Right now, I can identify are three things that draw me to Soderbergh’s body of work. The first is personal, and subjective: I identify with the professional restlessness that seems evident in his career, and his interest in practicing technique at every point of the production process. He’s famously worked as a screenwriter, producer, director, camera operator, cinematographer, editor, and even financier and distributor, often several at the same time. Ecumenical curiosity and an interdisciplinary approach appeal to me. The reason I started building my own websites—either last millennium or a millennium ago—was because I wanted an avenue to write, pencil, ink, collect, index, publish, and market my own stories.

The second draw is Soderbergh’s adoption of explicit creative constraint. I think there must be multiple reasons for that adoption, one of which is the desire to distinguish the pieces of work in a prolific career from each other.4I’m also a Mountain Goats fan, but that’s an essay for another time. The Ocean’s movies (2001-2007) look and feel different from Logan Lucky (2017) because even though they’re all ensemble heist-comedies, the former series uses handheld shots and zoom lenses in artificial light on saturated film, while the latter sticks to tripods, prime lenses, and natural light on digital cameras. I’ve been fascinated with constrained work for a long time.5Most often in terms of brevity: I’ve spent a lot of time writing microfiction, and twitter and vine once consumed a plurality of my attention. Soderbergh tends to talk openly about at least some of the formal decisions he brings to each piece of work, and I want to take the opportunity to trace those choices from outset to outcome.

The third has to do with trust. Even though I’ve only seen a minority of Soderbergh’s work at this writing, that’s still quite a few movies, and I’m always up for another one because in all that time he’s never let me down as a viewer. I can’t say that about all my favorite artists! But while, for instance, I didn’t enjoy Side Effects (2013), it wasn’t because I thought the film didn’t respect my time or my attention, or because Soderbergh didn’t seem committed to what he and his crew were making. If we set aside outright bigotry, then condescension and lack of commitment are the artistic failures I find most common, and most repellent.

What I do get from Soderbergh’s work is a certain expectation of respect, going both ways: he asks for the viewer’s trust that he’s got an interesting plan for what’s coming, and in return he offers trust that said viewer can follow the plan without being hit over the head. I think someone like David Lynch takes this a lot further,6I will say, though, that reading this interview excerpt changed my approach to abstract visual art forever. Sorry I can’t do any better than a Google Books link. to a point where I have little faith in my own ability to parse what he and his ensemble are doing. But Soderbergh’s offer is one I never hesitate to accept.

I’ve been trying to distill those three ideas for a few weeks now, so it’s convenient that I just watched a particular movie about trust, restlessness, and self-restraint.

I have tried not to analyze why this film was successful, for fear of trying to duplicate that success in a calculated fashion in the future. I followed my instincts, and so far they have served me well. Some people don’t believe (or understand) that for me the process of making a film is the reward.

from The introduction to the published script, p. 6, 1990

I don’t plan on summarizing plots on this blog, though I don’t plan on trying to dance around late-breaking story details either. If you want to keep reading and haven’t seen sex, lies, and videotape (1989), I can recommend Roger Ebert’s contemporaneous review, which stands up well aside from some inaccurate numbers in the concluding paragraph. Go refresh your memory about it, seriously, this blog will still be here when you close that tab.

When it comes to reviewing movies, I’m no Roger Ebert, even without deadlines and with decades of hindsight. So I don’t plan to focus on reviews here either, or on ranking favorites, not really. What I want to do is perceive and articulate each work’s individual framework of constraint, and how that framework functions. In addition to just highlighting the constraints Soderbergh has spoken openly about, I think there’s value in trying to figure out what rules are only evident from outside, and after the fact. A constraint that was intuitive and implicit in the moment is still an emergent property that changes the nature of the finished work, often in unexpected ways.

It’s pretty well accepted that the two fundamental boundaries on any large project, from the point of view of its creators, are its budgets of money and time. I’d add that a third one is the limits of your available technology. To make up for shortage of any of those three, you can lean on the others, up to a point and with diminishing returns. I don’t make movies, but I’ve spent my professional life assembling projects for one client or another at an hourly rate, trying to come in on deadline and under bid, and leaning on someone else’s machinery whenever I can to do so. So I know what an unusual challenge sex, lies, and videotape (1989) faced: after pitching his first feature script at a $60,000 budget, Soderbergh eventually had to accept a $1.2 million budget instead.

In his original plan, Soderbergh was going to shoot on black-and-white film, and indeed placed an order for 100,000 feet of 16mm negative before being persuaded that audiences would be distanced from the actors’ performances by the foregrounding of an unusual stylistic choice. That’s not a thing you have to care about when you’re making a personal project, but it is when RCA/Columbia is funding you. Beyond changing the immediate nature of the film itself, if the budget had remained in the five-figure range, then many fewer people would have seen the result. Maybe Soderbergh would be teaching screenwriting classes at LSU today, and I wouldn’t be writing this blog.

You can read some of Soderbergh’s thoughts on getting nudged into RCA/Columbia’s plan in his production journal, which is bundled with the movie’s script, long out of print but blessedly available to borrow through the Internet Archive’s digitization project. Miranda July, who credits the book as an inspiration, slyly asserts that one should consider its writer’s editing background when gauging whether all of those entries were written as they’re dated. I found it valuable nonetheless. It seems clear that expanding the budget by orders of magnitude didn’t make shooting sex, lies and videotape (1989) simpler, but it changed the nature of the problems to be solved.

For one thing, it seems that the financial backers were pretty surprised to see the first workprint and discover that the movie with “sex” in the title and an R-rated script contained no explicit nudity. Soderbergh suggests that part of their rationale for an expanded budget was that they figured, hey, if it sucks, we can recoup some of the cost by selling the late-night cable TV rights. Instead, Soderbergh had quietly conceded to Laura San Giacomo’s balky agent in adding a no-nudity clause to her contract, and then found on set that he felt uncomfortable directing even clothed sex scenes after bonding with his cast.7Perhaps I’m giving him too much credit, but it seems like he was anticipating the need for intimacy coordinators, a role which would not be standardized on film sets for another twenty-seven years.

For another example of the way the problems were transformed, we can look at the casting process. A microbudget movie is going to get cast with local talent, probably either your friends or their friends. I went to school for theater, and I know firsthand that unknown actors can be extraordinary. When you have a professional running your casting, though, and your budget compels you to pick leads with at least a hint of name recognition, you run the risk of balky agents, or of egos in conflict who can’t easily be replaced. But if you navigate those risks, you can get actors who have developed performing talent into the specific skill of collaborating with a camera.

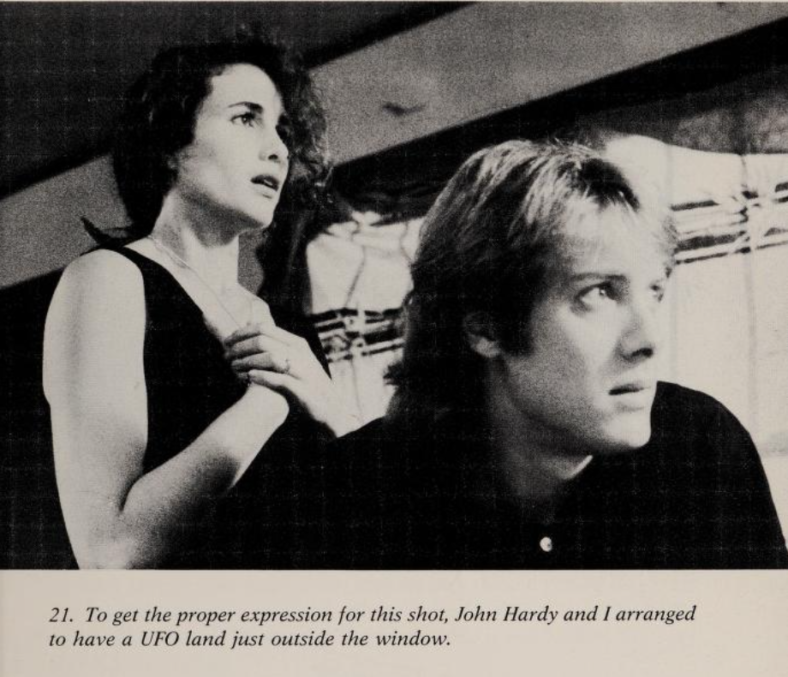

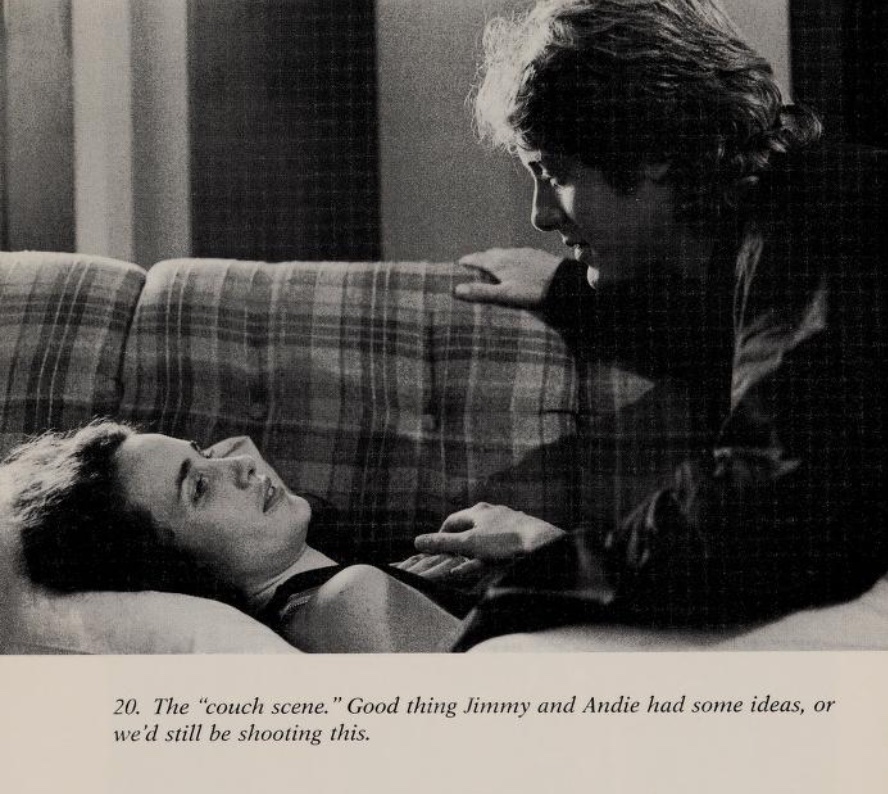

I learned from the set journal that a number of my favorite lines were improvised by the actors, even though the film wasn’t conceived as an improvisational piece. Directors change screenplays on the fly all the time, of course, but following an actor’s instinct to make that change is a specific choice, and it takes commitment. One place where the constraint on nudity and that freedom to improvise coincide is at the climactic speechless moment between Ann, the protagonist, and Graham, her antagonist. The blocking and business are all things the two actors—fully clad—came up with on the set that day. That scene has to work or the movie collapses, and it was left up to James Spader and Andie MacDowell to figure that out.

This is what I’m talking about when I say that adopting an intuitive constraint changes the outcome. I’ve already used the word “rule” once in this entry, but I think the idea that constraints and rules are interchangeable concepts is a fallacy. An imposed rule can certainly constrain, but creative and formal constraints aren’t rules any more than a hammer or a camera is a rule: they are tools for shaping work, and advanced work is impossible without them.

Here’s another example. From the shooting journal, the day they filmed MacDowell and Spader having lunch:

The scene went smoothly, although Paul went crazy with the traffic noise (“Don’t worry,” I told him) and Elizabeth Lambert made me aware of a myriad of continuity errors involving hand placement (“Don’t worry,” I told her).

August 8th, 1988 (p. 180)

And from the editing journal, which seems to demonstrate that Soderbergh comes by the title’s serial comma honestly:

WHY DIDN’T I LISTEN TO ELIZABETH LAMBERT? The cafe scene (16) was a nightmare! Hand, arm, and wine-glass positions didn’t match from one take to another, just like Elizabeth said and noted in her lined script. … After testing various edits, it became apparent that due to continuity problems, I had to hold on angles for a while so that you quit looking for matching fuck-ups. Of the ten pauses that seemed to mean so much while we were shooting, six of them now seem interminable. There’s a fine line between naturalistic dialogue and dialogue that is SO realistic it puts you to sleep.

October 16th, 1988 (p. 208)

What does this mean? Well, the scene is an intimate one, in which the camera closes in on Ann and Graham as the two make some awkward disclosures and start to discover an interest in one another. A standard shot sequence might look like this, if an inept editor like me didn’t have to worry about continuity or dialogue: seven cuts in thirty seconds.

But what does the actual scene look like? The first five cuts take almost three times as long:

First, did you notice MacDowell’s hand jump down to the table at the start of the third shot? It happens in both versions, but I notice it in my recut in a way that I didn’t in the original: Soderbergh is right to say that holding the shot lessens your awareness of it. I think he might be pretty good at editing.

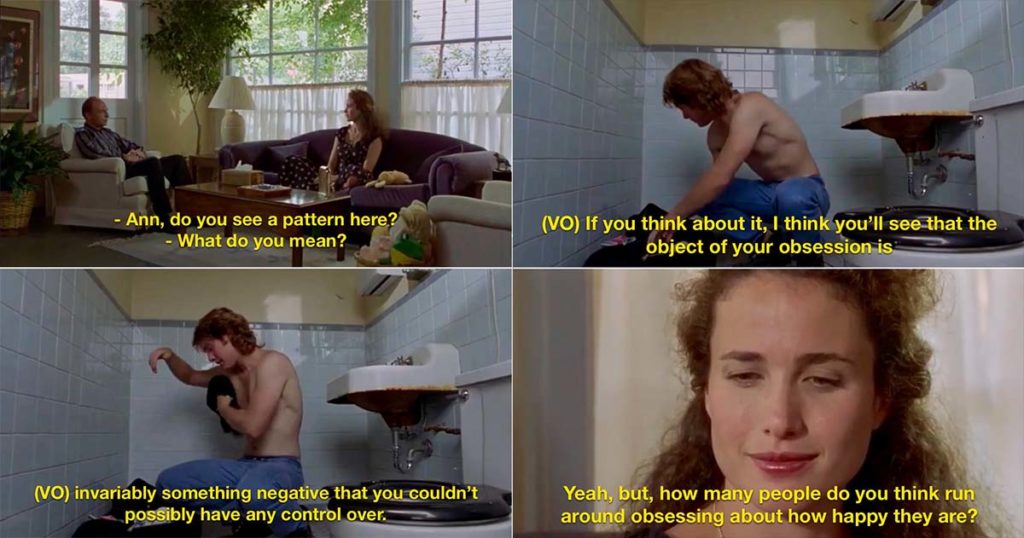

Second, I think of long static takes as a tacit request for sustained focus, which means the latter of these edits asserts itself as a choice to the viewer in a way that the former doesn’t. And that assertion isn’t usually what you want from an edit! Certainly not if the editor’s job is to be invisible, which is often the case. But the editor’s other job is to let emotion register, and given the tension of the holds on each actor’s face, you see why Ebert suggests that this film’s thesis is about conversation being more erotic than sex.

Even though this series of choices was born out of mistakes and frustration, it’s not the only time in the movie where a suspended beat becomes… well, suspensful. It actually mirrors Graham’s video technique, where he keeps focus on his interlocutor’s face while his voice comes from offscreen. A constraint enforced on one scene becomes a tool guiding the pace of the whole story.

Similarly, I think of a typical J-cut8An edit in which the audio from the upcoming shot overlaps before the visual change occurs, helping the audience anticipate the transition. as lasting a second or two, just enough time for you to register the upcoming transition. Soderbergh not only likes to hold on his outgoing visual for closer to five seconds before finally completing the cut, he sometimes cuts visually and then reverts to the original shot without ever playing the insert’s audio: a kind of U-cut, which you can see in the very first scene of the film.

The other thing you can see in the first scene, just for a few frames, is Graham’s Sony video camera. Like the playwright’s gun, you know it has to start shooting eventually. You know from the title that it’s being framed as one of three things with inescapable consequences. And this is the part where we pick up that thread from earlier, about Soderbergh—who has always reached for the newest recording instrument that meets his standards—and the limits of available technology.

When you record someone on a 1989 video camera, even a nice one, and then record the playback of that video off a monitor onto film, there’s a word for the quality of the resulting image: the word is degraded. It’s not a word that appears in the script of this movie, but its double meaning is everywhere in the other characters’ interpretation of Graham’s recordings of women discussing sex. Cynthia the libertine is eager to explore that meaning, but Ann and John—who is a libertine himself—each display horror at the concept, at one point or another.

The word horror is an important one too. Both the tension of the long takes discussed above and the aesthetic of flickering, grungy video carry hints of a horror film, something Soderbergh openly evokes in his production diary. It’s a curious inversion of the move away from monochrome film; that could have been a visual signifier that distanced the audience by suggesting reservation. But the distance offered by degraded analog media can perversely heighten emotional involvement and adrenaline by locking someone you care about away, beyond a screen and a time warp, where you can’t reach them. If you saw these ten seconds out of context, why might you guess that John looks stressed out?

To me it reads like someone watching video of a hostage or a victim. In the actual context, of course, Ann is fine, and John is the one feeling victimized by her decision to leave. In a way he is horrified, or at least sickened. But it’s a horror that arises from the costs of his behavior coming due. She’s the subject of the tape, but he’s being made subject to the consequences of his decisions.

It’s hardly groundbreaking theory work for me to say that sex, lies, and videotape (1989) posits the ubiquitous consumer-grade camera of the 1980s as a wedge that alienates people from each other. But Graham’s Handycam doesn’t just repel Cynthia, Ann, and John, it also compels them each to pursue him in some way, when their respective feelings toward him crest the boundaries of his isolation. The technology doesn’t nullify emotions so much as it puts them under pressure.

If this were a horror movie, then Graham would seem to be the monster.9I mean, he is a mysterious and deviant figure in black with hidden motives and a signature weapon —I think one of the models in the CCD-FX series—that he uses to disrupt the other characters’ lives. And the film does indict him for his actions, when Ann turns the camera back on him, making him cower from the lens as she flares. This is a story about how observation changes the observer, and in some hands, that would lead up to a trite moment where a character stares right down the barrel and says, hey jerk, aren’t you the real voyeur here?10I hate this device, but Tampopo (1985) reminds me that it can be done well.

But that kind of thing is almost always a failure of respect for the audience. I think it’s priggish and hypocritical to scold your viewers for watching the thing you spent your ad budget telling them to watch.11Or to play, as video games have started doing this too. This movie’s script started out as a way for its writer, by his own account, to divide up, examine, and excoriate his own worst impulses. As someone who has been blogging for twenty years, I can relate to that. But if that were the extent of the final work—if it were, as some have speculated, equally suited to production as a stage play—its broad and lasting acclaim would never have materialized.

Instead, Soderbergh and his team took the tools they were given and built something that made people take notice. The predominant lack of music was chosen deliberately, so that when first-time composer Cliff Martinez’s score does surface, it’s specific and effective: after the guitar that plays over the road shot at the very beginning of the movie, the film waits for a full quarter of its runtime before its second music cue. Meanwhile, the constraints that ruled out nudity and that privileged the actors’ line contributions over the printed script arose from the instincts that led the film to success.

Constraints of budget and editing rhythm were imposed on the film, as much as they were selected, but then they were considered and incorporated, made part of the final whole. And the inherent limitations of the camera—making it so easy to capture a moment, and so hard to be present within it—shape both the film’s message and its mixture of media.

I assert the common factor among them all is trust: in a crew with more expertise in their fields than a 26-year-old director, in a cast with the chemistry and agency to be more than the sum of their parts, and in an audience that the film is asking to step inside its magic circle, once its creators have done their best to make that step… well, Soderbergh said it himself.

To me, making an idea accessible doesn’t necessarily mean dilution or compromise; it can mean clarity of execution.

from The introduction to the published script, p. 7, 1990

All right. This is the longest thing I’ve written in years, but I don’t expect to spend as many words on groundwork for future entries. I do hope you find this framing as useful and interesting as I do. I know I said I wasn’t going to write reviews here, but I’ve enjoyed this movie more the longer I spend writing about it, even though I only saw it for the first time a week ago. Give the Criterion remaster a try, with the caveat that some of the characters’ speculations on gender have aged poorly. I bet your library will lend you a copy.

If you read all the way to this point, then thank for trusting me with your time and attention; I promise to respect them. This blog doesn’t have comments, but I love talking about movies via email. If you want to read future entries, I will reluctantly tweet about them, but I also encourage you to subscribe to the feed with your reader of choice.

- 1Rian Johnson. Sorry.

- 2Hackers (1995).

- 3As if there’s any doubt.

- 4I’m also a Mountain Goats fan, but that’s an essay for another time.

- 5Most often in terms of brevity: I’ve spent a lot of time writing microfiction, and twitter and vine once consumed a plurality of my attention.

- 6I will say, though, that reading this interview excerpt changed my approach to abstract visual art forever. Sorry I can’t do any better than a Google Books link.

- 7Perhaps I’m giving him too much credit, but it seems like he was anticipating the need for intimacy coordinators, a role which would not be standardized on film sets for another twenty-seven years.

- 8An edit in which the audio from the upcoming shot overlaps before the visual change occurs, helping the audience anticipate the transition.

- 9I mean, he is a mysterious and deviant figure in black with hidden motives and a signature weapon —I think one of the models in the CCD-FX series—that he uses to disrupt the other characters’ lives.

- 10I hate this device, but Tampopo (1985) reminds me that it can be done well.

- 11Or to play, as video games have started doing this too.