In the former half of his career—which I’m counting as the first 20 entries in this list—Steven Soderbergh adapted between four and nine books for the screen. The actual number depends on how narrowly one defines the concept of adaptation. Kafka (1991) blended elements of The Castle and The Trial with elements of its subject’s life; The Underneath (1995) remade Criss Cross (1949), which was itself an adaptation of a Don Tracy novel; Out of Sight (1998) adapted Elmore Leonard, while The Good German (2006) adapted Joseph Kanon; and Solaris (2002) remade Andrei Tarkovsky’s film 1972 film, itself an adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s novel.1In the latter half, from 2007 onward, Soderbergh’s interest in book adaptation seems to have run its course—only The Informant! (2009), Behind the Candelabra (2013) and The Laundromat (2019) would qualify. He didn’t write any of them, and indeed ceased writing screenplays entirely after 2006.

The number rises if you count adaptations that never made it to production, as well. After his early success, interest around Soderbergh involved his scripts as much as his direction. In 1990, he wrote several adapted drafts of William Brinkley’s novel The Last Ship for production by Sydney Pollack, and in 1996 he wrote drafts of Carol Hughes’s book Toots and the Upside Down House for director Henry Selick. Neither was ever made. In between those, Soderbergh and Scott Kramer found themselves pursuing a legal battle in the long, discouraging history of attempts to adapt A Confederacy of Dunces: Nathan O’Hagan says Soderbergh’s own script “came closest to ever seeing the light of day” of all the attempts so far. (It got a single staged reading.) In 2009, for his last crack at the work of writing a book adaptation, Soderbergh produced a shooting plan and a draft script for Michael Lewis’s Moneyball which, it is said, together so aggravated Sony Pictures chair Amy Pascal that the movie was put into turnaround.2“When all the Moneyball stuff happened, people said, ‘Wow, you must be really pissed off.’ I said no, not really; it means I’m still capable of scaring people. That’s a good thing. That means I’m still enough of a crazy person to make somebody pull the plug.” —Soderbergh to Mark Gallagher, Another Steven Soderbergh Experience, 2013

And then there’s King of the Hill (1993), a memoir by A. E. Hotchner, both the first book Soderbergh ever adapted, and the only direct book-to-screen script he would ever take to production himself.3Soderbergh did script The Underneath (1995) and Solaris (2002), but both have that intermediary-movie asterisk. He does not seem to have enjoyed that part of the process.

“To think back on that period of writing the script, I can remember where I was… I was working out of this little smokehouse on the farm in Virginia, outside Charlottesville. I had one of the old Macs, like a Mac II? It just reminds me how much I didn’t like writing. How you’re just all alone. And you’re just constantly sort of crashing into the barrier of your own ability. So I just have this memory of days spent out in this little smokehouse, sort of staring at the screen, trying to solve, you know… the problems that any movie needs to have solved, and yet trying to keep it from being something that, Hotch would look at and go ‘well, that’s just crazy,’ you know, ‘that doesn’t bear any relation to what happened to me.’ I was very conscious of that.”

Soderbergh, in a featurette on the 2014 Criterion release of King of the Hill

The farm he refers to in that quote is the one he bought two months after winning the Palme d’Or, in 1989, and where he subsequently married and lived with actor Betsy Brantley. The two would divorce in the fall of 1994, and whether that event was connected to Soderbergh locking himself in a smokehouse and feeling “all alone” is beyond the scope of my speculation.

But his description does tell us some things about the constraints on the project from its outset. Soderbergh wanted to write, direct, and edit the film himself; he wanted to make its story fit into a three-act structure; and he wanted the resulting period piece to retain its resemblance to the childhood experience of its author.

If you’re not a follower of his work, then Hotchner may be best known by association: in addition to teleplays and novels, he wrote popular biographies of his friends Ernest Hemingway and Doris Day, and cofounded both the Newman’s Own brand and the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp it supports with his neighbor Paul Newman. Hotchner was 102 when he passed away in 2020—a remarkable life for someone who could well have died in childhood several times over during the events of his 1972 autobiographical novel.

Here’s an effusive Goodreads review and summary of King of the Hill, which many sources describe as a Bildungsroman. The author certainly seems to have viewed it as a story of adversity overcome by youth, and it has an aw-shucks vernacular to its prose which lends it a chipper tone of scrappy pluck. To me, the actual plot comes across more like horror. I know the expected standards of care for children have changed a lot since the Great Depression, but some of the experiences described in the book would be considered harsh for a gulag. It takes place over the course of a St. Louis summer wherein its protagonist turns 13. The title is not explained in the film, but here’s the segment from the book that gave rise to it:

“It was like a mud slide coming down on you one slide after another. I knew about mud slides, all right. When we had lived on Concordia Lane in South St. Louis, there was a mountain of clay nearby where a brick factory operated. Us kids played on the mountain and dug caves in it and climbed all over it. But one afternoon after school, when it had been raining for a couple of days, we were out on the mountain in our rain clothes playing King of the Hill when the gooey mud at the top got unstuck and started to slide down on top of us. We scrambled around and got out of the way of it, but another slide was coming right on top of the first one and then another, and two of the kids got buried in it. We tried to dig them out but the mud kept on sliding down from the top. The workmen at the brick factory were all gone home, so we had to do the best we could. There was one gigantic slide that buried all of us, which was more scary than anything you can imagine, but we dug ourselves out of it and kept on trying to find those first two kids. We finally found one, a skinny little seven-year-old who shouldn’t have been playing with us nine-year-olds in the first place. He was more scared than anything else, and when we dug the clay out of his nose he was all right. But we couldn’t find the other kid, and by the time help came and they found him and rushed him to the hospital, it was too late.

So you can see I know about mud slides.

King of the Hill, Hotchner, ch. 28

A number of critics were mystified by the choice to make a PG-13 movie about a 12-year-old kid—a story that includes ostracism, violence, suffering and suicide. Soderbergh himself sees a straightforward theme running through this and his previous movies, though. “When I look at the film now,” he says in the same Criterion featurette quoted above, “it seems to fit in a larger context of protagonists who, through sheer force of will, are trying to kind of make the world work the way they want it to work.”

As usual, I’m not going to be summarizing the plot here, but either the book review or the movie review linked above will give you a good start if you’re not familiar with the story; I encourage you to take a moment to spoil yourself before continuing. The film is not currently available for digital rental, but it appears on the Criterion Channel intermittently, and there are always other options.

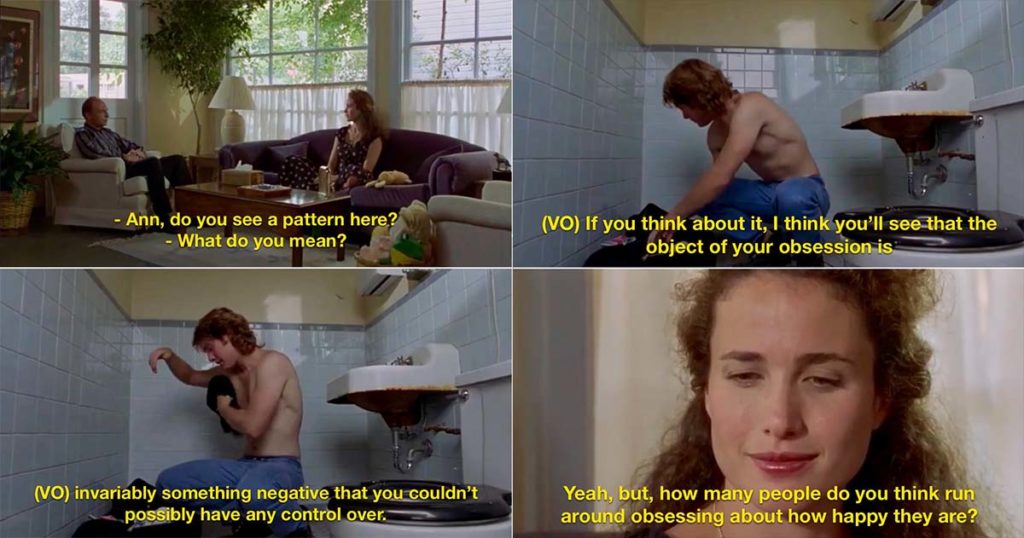

Soderbergh’s choice to adapt this specific novel would end up entangled in his early relationship with Robert Redford—who, in turn, was only one step removed from Hotchner by way of his own relationship with Paul Newman. sex, lies, and videotape (1989) had debuted at Redford’s Sundance so early in the festival’s history that it wasn’t even called Sundance yet, and Redford had taken an interest in Soderbergh’s career, at one point being attached to King of the Hill (1993) as a producer. That promising connection dissolved before the movie was finished for reasons that neither party has talked too much about.4One of the events in that dissolution was that Soderbergh had the script for Quiz Show (1994) offered to him, accepted it—and then saw the offer rescinded in favor of Redford, about which he learned only secondhand.

A thesis I might have to explore one day is that Soderbergh’s ability to navigate and commit to professional relationships has been as critical to his professional longevity as any other talent. The commitment, in turn, seems to come from the fact that those relationships really matter to him. I think it’s possible that frustration of his experience with Redford, added to bitter litigation over the aforementioned Confederacy of Dunces adaptation, would eventually combine to send him careering out of Hollywood entirely and into independent work for the self-excoriating reinvention described in his book Getting Away With It.5His attempt, one might say, to make the world work the way he wanted it to work through sheer force of will. He didn’t end up working with Redford’s Wildwood Pictures at all, and instead stuck with Casey Silver at Universal’s Gramercy arm, which would lead in time to Soderbergh’s second breakout with Out of Sight (1998). Silver and Soderbergh are still working together, 30 years later.

But back in 1992, what did Silver help Soderbergh get away with? Somehow, at once, the studio trust that comes with high expectations and the benign neglect that comes with low ones. King of the Hill (1993) failed at the box office, but Universal kept investing in him for years to come.

“The reason I haven’t yet turned into a cult failure is because I’ve yet to make a film that people have expected to make a lot of money. So, until I make a $40 million movie with stars in it—which is conceivable—that is expected to make money and then doesn’t, people’s perception of me is not going to be anything other than an interesting, responsible young filmmaker.”

“Whatever happened to Steven Soderbergh?” in Premiere magazine, January 1994

“Conceivable” is an understatement now, but it was only just true back then.6Five years later, he did in fact make a $48 million film with stars in it—George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez, no less—that recouped its budget but lost money against its marketing costs. But by then, on the verge of the dual-Oscar juggernaut of Erin Brockovich (2000) and Traffic (2000), cult failure was not an option. Soderbergh was making exactly the movies he wanted to make, borrowing against a single success that was already four years old, and doing so by threading his plans through a narrow constraint: use as much of someone else’s money as you can without making them worried.

King of the Hill (1993) had a production budget of around $8 million. For a period feature with a large cast shot on location,7Shout out to St. Louis, one of the greats, home to some wonderful people and among my favorite places to visit. Soderbergh on St. Louis: “I never saw so much brick in my life!” even three decades ago, that’s tight; the cost of film stock alone would have run into six figures, though Soderbergh and veteran cinematographer Elliot Davis8Davis and Soderbergh continued working together on the features Soderbergh made for the remainder of the 1990s; from 2000 onward, Soderbergh has almost always worked as his own DP. eked out some savings there by means of the Superscope 235 format and the inexpensive lenses it permits:

“I didn’t want it to feel like a little indie thing. I wanted the audience to feel comfortable and feel like it had the craft level of a normal studio film. I didn’t want it to come across as something that looked cheap. As it turns out, shooting Super 35 is a very inexpensive way to make something look expensive.”

Soderbergh, Criterion featurette

I’ve been waiting to deploy the phrase “formidable constraints” for like 1700 words now, so there it is: what we’ve outlined so far is already a very specific space in which to produce a movie. That space continues to narrow when we consider that producing an “expensive-looking” film about the Depression risks some tonal dissonance, something Soderbergh now acknowledges.9The faint golden haze that overlays much of the film was Soderbergh’s first experiment with suggesting emotional atmosphere by way of color timing, a technique he’d use often in the decade to come. But he was still trying to prove himself, and prove that he could do work in a visual medium at the same level as the artists he admired. With his team of Davis, costume designer Susan Lyall, and production designer Gary Frutkoff, Soderbergh worked to evoke the saturated off-primary colors of American oil painter Edward Hopper, but in interviews, he was eager to discuss European movies as his points of reference.

I really thought I’d caught a break when I came across one particularly specific quote, from an interview in Positif magazine that Soderbergh gave to Michel Ciment and Hubert Niogret (with translation by Paula Willoquet). Another thesis for this site that I have half-pocketed right now is that Soderbergh’s great trick is approaching distinctly American stories with a perspective grounded in his love of Western European film. So when I read him talking to French journalists about the specific French, Swedish, and Italian movies he referenced, I thought I could put together one of those cool comparison videos that shows you exactly which shots are borrowed from where. Part of the reason this post has taken so long is that I kept giving myself more homework.

What I found instead, after watching them each a few times, was that Soderbergh and Davis had anticipated and outmaneuvered me. Instead of borrowing shots, they noted the way previous films had approached children in situations beyond their years, then inverted those approaches, sometimes literally.

Aaron, the protagonist of King of the Hill (1993), isn’t a kid striking out on his own like Antoine Doinel of The 400 Blows (1959), or one gaining a new perspective on his family through trauma like Ingemar of My Life as a Dog (1985) or Billy Rowan of Hope and Glory (1987). He’s forced to take on the role of each adult he knows, one by one, as those erstwhile guardians are whittled away from him by the mounting austerity of his world. Where other child protagonists run away, lash out, or take refuge in fantasy, Aaron stubbornly stays put, takes on too much responsibility, and tries to pass off his daydreams as cover stories with the adults who might expose his tenuous situation.

There are set pieces in the book—baseball games, a mule-drawn chariot race, and a bull stampede that turns into a mass shooting—that didn’t make it into the movie, because an $8 million budget has its own austerities. But they’re also eliminated by a different constraint: they don’t serve the narrative arc of Aaron’s increasingly Dickensian difficulties.

Soderbergh and Debora Aquila, who had also worked together on sex, lies, and videotape (1989), found actors for their adult cast who would have looked right in place as woodcut profiles for a Victorian serial novel.

No doubt you spotted Spalding Gray as the doomed Mr. Mungo up there, whose role stands in for several of Aaron’s neighbors in the book. He leaves a strong impression, playing his character with charming and enigmatic skill. But I don’t think there can be any doubt that the real ringers are the younger cast.

That’s Adrien Brody five years before The Thin Red Line (1998), Amber Benson six years before she joined Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Katherine Heigl six years before Roswell, and Lauryn Hill the same year the Fugees were signed and just before Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit (1993) began shooting.

But it’s Jesse Bradford, only two years out himself from a high-profile role in perhaps the greatest motion picture of all time, who was given the task of carrying the film. Appearing in every scene, it’s his job to win sympathy without steering into twerpiness or schmaltz. Since Aaron often tries to cope with shame and fear by making up stories, Bradford has to convey that he’s thinking on his feet and preparing a lie that an adult won’t quite challenge, and he has to do it using only small gestures and facial expression. That’s due to a constraint I found very welcome: King of the Hill (1993) has no voiceover.

Hotchner’s book is written in first person with a distinct voice for its narrator, so it would have been simple to put that voice right into the script—another director might even have had Hotchner read the narration himself. But by discarding that option, Soderbergh’s film can more easily keep the audience’s attention on the work of the actors onscreen. You can see it in this deftly acted exchange between Bradford, a new school friend played by Chris Samples, and that friend’s mother, played by Peggy Friesen. If you know that Aaron’s family lives in poverty, and this family doesn’t, do you need a voiceover to detail what’s running through his mind? Or do your eyes tell you what’s happening in the scene?

If you made the opposite of every directorial choice in this movie, I think you’d get something much like its contemporary, The Sandlot (1993): a shaggy, rambling PG movie about kids and for kids, guided by a chuckling narrator who lets you know from the outset that things are going to turn out all right, where every adult’s stern facade hides an indulgent heart of gold. The two films even share a chase sequence featuring a sprinting older-brother figure and a maternal role by the great Karen Allen. This isn’t to scorn The Sandlot (1993), which I enjoyed when I last saw it. I just think it’s interesting how you can take tonally similar coming-of-age material, apply different constraints, and get very different work for different audiences. The opening paragraph from King of the Hill could have fit right into a treatment for a genial baseball movie:

Last summer really started May 9th, the day they put the lock on 326. You may think May is too early for summer, but let me tell you, not in St. Louis. In geography we studied about the equator running through Africa and all that, but believe me St. Louis is the equator of the U.S.A. The St. Louis sun passes through about three hundred magnifying glasses. You keep a candle on the bureau, and once that St. Louis sun really gets going the wick is right down tickling the bureau top. And that’s what it does to your brain. Melts it down, and if the brain had a wick, by July it’d be tickling your eyebrows. The only good thing about the St. Louis sun is when it really gets going it melts the streets and you can just dig a finger in and scoop out a hunk and chew the black tar same as Wrigley’s.

Hotchner, King of the Hill, Ch. 1

I hope you see what I mean now about the aw-shucks vernacular. This is a passage rich in peppy nostalgia. It’s also a description of a child trying to endure extreme heat by eating asphalt. Over the course of the story, Aaron resorts to eating worse than that to cope with his circumstances, as seen below.

He never experienced the kind of deprivation that Aaron endures in the clip that opens that excerpt, but in his own way, Soderbergh was young and hungry too. I wonder what he thought about, trying to sort out the paper-dinner scene on his Mac II in his Charlottesville smokehouse. I myself look at it and see an object lesson: no matter how pretty you make your picture, at the end of the day, you can’t eat art.

In retrospect, Soderbergh would attribute the movie’s failure to attract attention during its Cannes screening to the fact that, in his words, it “doesn’t have a political issue” to center on. Even the book review I linked above describes the story as “never polemic.” But Hotchner’s work, and Soderbergh’s too, is sharply critical of the world it depicts, and in 2022 that seems more evident than ever. That wasn’t missed at the time of its production, either.

King of the Hill has an obvious timeliness despite its period setting. “I loved the way it correlates to today — the parallels between 1992 and 1933,” says Lisa Eichhorn, who co-stars as Mrs. Kurlander. “I think it’s very depressing out there today, and it’s very hard on families.”

“When Hollywood Met St. Louis… A Look Back at the 1992 Shoot of King of the Hill” in Cinema St. Louis, December 2020

The existential menace of the story is housing insecurity: Aaron’s family is long behind on their rent for the single hotel room they share, and the bellboy-enforcer’s padlocks are the tools of seizure, descending one by one on his neighbors when they make the mistake of stepping outside their doors. The hotel can’t legally confine anyone against their will, so keeping someone in the room at all times is the only way to stave off eviction and the loss of all their belongings. When his mother has to seek care in a sanatorium and his father abandons him for a watch-sales route, Aaron becomes a solitary and starving prisoner, choosing to endure life-endangering torture rather than abandon his post.

Earlier in the book, Aaron observes a Hooverville camp en route to a one-time gig selling stockings to a group of kind sex workers, knowing the shantytown will be the only place left to go if the hotel room is lost. In the movie, Soderbergh places the camp directly across the street from the hotel, and shows the police sweeping it to further displace its residents, a practice that hasn’t changed in 90 years. One of Aaron’s two most direct antagonists, in fact, is the local police officer, whose side hustle includes harassing Aaron in exchange for bribes from the men trying to repossess his father’s car. I mentioned earlier that the book includes a sequence with escaped bulls leading to a mass shooting—that’s the same Patrolman Burns at work, firing indiscriminately into the crowd leaving a synagogue10Jewish people are more than victims in the story. I found it affecting that several of Aaron’s positive experiences in the book are specifically with Jewish characters—his friend and role model Lester Silverstone not only goes to great lengths to help him, but invites him along to a bris for a rare full meal, while another friend invites him to join a youth group at Temple Israel, and his father’s supervisor Sidney Gutman is a benevolent figure in his brief appearance. It’s a notable choice for a memoir set in the 1930s. on the chance that he might hit some of the animals.

Burns is rewarded with a medal for his actions. Some other things haven’t changed in 90 years, either. (Did you know that the number of US children living in poverty increased by 3.7 million between December of 2021 and January of 2022, thanks to austerity measures by the federal government?) This is far from an apolitical story. Other readers have compared the book to Tobias Wolff and Betty Smith; I found myself thinking of Ursula Le Guin.

In the video embedded above,11You only get to see it for a second, but at 0:45 when Burns is shown holding Aaron’s ear, there’s a little background Easter egg: the movie playing on the marquee is Laughter in Hell, a controversial 1933 pre-Code drama about prison abuse. As of 1993, the film was presumed lost, but in 2012, a preserved copy was rediscovered and screened. Soderbergh describes Hotchner’s story as having “a nice landing—this kid gets sort of caught up in a tree, and people throw rocks at him for three acts, and then you get him down at the end.” Part of making a Hollywood movie is adjusting things for a Hollywood ending: Burns gets some comeuppance for his harassment instead of a medal, one of the Hoovertown residents gets his means of living back, and the cruel bellboy gets his padlocks taken away. Maybe that same bias toward softness informed the wistful plucked-strings score, by returning composer Cliff Martinez, whose work is put to more liberal use than when he scored sex, lies, and videotape (1989).

That embrace of the “nice landing” may not seem at first like a constraint, but of course it is, and it’s one piled atop the dictates of creative process, medium, budget, audience, casting, narrative options, visual palette, aesthetic standards, oversight avoidance, and authorial allegiance we’ve already outlined. All of these were choices, not impositions, and all of them were as constructive as they were limiting. But sometimes, after finishing a piece of work, one can look back and decide the job needed different tools.

There’s one more constraint I haven’t mentioned yet: the film’s length. The first cut of the movie was over two hours, and Soderbergh went back in to the editing suite after a preview screening and carved out half an hour of the narrative. But then, in the final week before sending the reels to print, he went in again.

“At the time, for some reason, I was very obsessed with this idea of 100 minutes. Like, the first four movies are almost all exactly 100 minutes long. I don’t know where this came from. But I ended up making a lot of cuts, late in the process of King of The Hill, to get the movie down around 100 minutes. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s something as lame as my understanding that if you make a movie that’s 100 minutes long, you can screen in a theater every two hours. Certainly I’ve always been someone who’s tried to lean more toward shorter than longer, but I remember that after the movie came out and didn’t succeed commercially, I thought, why did I do that? Why did I go in in the last week before we really had to lock it and cut, I don’t know, six or eight minutes out of it, thinking that that was going to make any difference? I should have just left it the way it was and let it play.”

Soderbergh, Criterion featurette

There’s no way to know whether keeping those six minutes, or scuffing up the look of the film, or marketing it as a politically relevant story would have made a difference in the critical or commercial fortunes of King of the Hill (1993). There’s no way to know what Redford’s continued involvement with the project could have meant for the direction of Soderbergh’s career, either. The film is nearly now thirty years old, adapted from a book twenty years its senior, chronicling events that took place forty years before that. Every depiction of history becomes history itself.

Back when The AV Club was a pretty good website, I came across a random comment12“You know someone named Arsenio Billingham?” on the excellent Tasha Robinson’s A-minus review of The Informant! (2009) that I find myself thinking about more often than its nature perhaps warrants.

Serious question! So, I keep hearing about the brilliance of Soderbergh, but every time I read a review for one of his movies, it’s for a film that’s either pretty good [or a] significant misfire. Are there any stone-cold classics in his canon, and if someone’s never seen his movies, where would one begin?

Arsenio BillinghaM

For one thing, “pretty good or a significant misfire” could be both a critical summary of King of the Hill (1993) and an intriguing Tinder bio. There are some candidates for classics suggested in the replies to that comment, and I wonder whether the writer decided to try any of them. But for another thing, even if one takes the question in good faith, it presupposes a certain fixed mindset when it comes to enjoying creative work. Why conflate “where to begin” with “stone-cold classics?” Nighthawks is the way many people first experience Edward Hopper, but it’s not the entrance exam, and you don’t have to read The Left Hand of Darkness before you’re allowed to show an interest in Ursula Le Guin. No amount of homework can optimize your experience of art before you try it. But on top of that, I’ve already quoted Soderbergh on his view of the matter:

Some people don’t believe (or understand) that for me the process of making a film is the reward.

I think the popularity of livestreaming in 2022 demonstrates that just watching someone else do skilled work can be rewarding in its own right, regardless of the outcome. The sustained critical curiosity about Soderbergh shows another reason to place that priority on process: a misfire isn’t the same thing as letting your audience down, and as long as they’re not let down, they’ll keep paying attention. I certainly appreciate your attention to my process of working through these movies, which sometimes take me longer to write than their director needs to make them. Maybe for the next post, I’ll try to see if things move faster when I’m tackling one I don’t actually like.

- 1In the latter half, from 2007 onward, Soderbergh’s interest in book adaptation seems to have run its course—only The Informant! (2009), Behind the Candelabra (2013) and The Laundromat (2019) would qualify. He didn’t write any of them, and indeed ceased writing screenplays entirely after 2006.

- 2“When all the Moneyball stuff happened, people said, ‘Wow, you must be really pissed off.’ I said no, not really; it means I’m still capable of scaring people. That’s a good thing. That means I’m still enough of a crazy person to make somebody pull the plug.” —Soderbergh to Mark Gallagher, Another Steven Soderbergh Experience, 2013

- 3Soderbergh did script The Underneath (1995) and Solaris (2002), but both have that intermediary-movie asterisk.

- 4One of the events in that dissolution was that Soderbergh had the script for Quiz Show (1994) offered to him, accepted it—and then saw the offer rescinded in favor of Redford, about which he learned only secondhand.

- 5His attempt, one might say, to make the world work the way he wanted it to work through sheer force of will.

- 6Five years later, he did in fact make a $48 million film with stars in it—George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez, no less—that recouped its budget but lost money against its marketing costs. But by then, on the verge of the dual-Oscar juggernaut of Erin Brockovich (2000) and Traffic (2000), cult failure was not an option.

- 7Shout out to St. Louis, one of the greats, home to some wonderful people and among my favorite places to visit. Soderbergh on St. Louis: “I never saw so much brick in my life!”

- 8Davis and Soderbergh continued working together on the features Soderbergh made for the remainder of the 1990s; from 2000 onward, Soderbergh has almost always worked as his own DP.

- 9The faint golden haze that overlays much of the film was Soderbergh’s first experiment with suggesting emotional atmosphere by way of color timing, a technique he’d use often in the decade to come.

- 10Jewish people are more than victims in the story. I found it affecting that several of Aaron’s positive experiences in the book are specifically with Jewish characters—his friend and role model Lester Silverstone not only goes to great lengths to help him, but invites him along to a bris for a rare full meal, while another friend invites him to join a youth group at Temple Israel, and his father’s supervisor Sidney Gutman is a benevolent figure in his brief appearance. It’s a notable choice for a memoir set in the 1930s.

- 11You only get to see it for a second, but at 0:45 when Burns is shown holding Aaron’s ear, there’s a little background Easter egg: the movie playing on the marquee is Laughter in Hell, a controversial 1933 pre-Code drama about prison abuse. As of 1993, the film was presumed lost, but in 2012, a preserved copy was rediscovered and screened.

- 12“You know someone named Arsenio Billingham?”