Before we begin, I’d like you to know that this entry touches on the subjects of suicide; eye injuries; and, in a secondhand way, the Cambodian genocide of the 1970s. In addition, I’m no expert on this, but I perceive some of Gray’s material as stereotyping and othering people when discussing his travel in Southeast Asia.

Steven Soderbergh made two movies about the late actor and monologuist Spalding Gray. He and Gray made the first in active collaboration, during Gray’s prime, called Gray’s Anatomy (1966); they made the second, And Everything Is Going Fine (2010), in retroactive collaboration, as Soderbergh and editor Susan Littenberg assembled it from Gray’s archives in the years after his death. In his career, Gray developed a novel method of work, combining memory, extemporaneous speaking, improvisation, and what he called “poetic journalism”—as in, both reporting experiences and working from his actual journal—to create a storytelling style that made many people feel that his personal narratives were universal, or at least highly relatable.

Gray inspired many descendants to follow his technique and adopt his tone. When I sat down to watch the first of these movies, his name was vaguely familiar to me, but I knew almost nothing else about him. Maybe you’re a connoisseur of Gray’s work, or maybe you’re in my situation. Even in the latter case, though, if you’re the kind of person who reads blogs, I bet you’re familiar with the work of one of his most famous artistic heirs.1You may wish to know, before viewing the following, that both men were fond of invoking stereotypes about Jewish women when discussing the wives they would later divorce.

I don’t want to go too far afield here, but Mulaney2Who, by funny coincidence, shares the pronunciation if not the spelling of his name with John Mullany, the villain of sex, lies, and videotape (1989). has acknowledged this lineage himself, and even wrote the episode of Documentary Now! parodying Gray—though the person who made the connection for me was Soderbergh expert and prolific, thoughtful film reviewer The Narrator Returns. I think the clarity of that heritage alone demonstrates a contrast between Gray and Soderbergh, who became good friends. Gray’s voice was so unique and consistent that he can be recalled just by following his timbre and cadence; Soderbergh, famously, has evaded identification with any single voice. Even these two films, which consist mostly of the same man talking to the camera, are the products of distinct visual stylists.

But at the risk of yet further scope creep, I should disclose that this essay is about three movies, not two. Soderbergh’s Gray films, and indeed the latter half of Gray’s career, all exist in the shadow of Swimming to Cambodia (1987). Directed by Jonathan Demme, it was Gray’s mainstream breakout and his first feature-film monologue.

When I saw Swimming, I had the sensation that I assume a lot of people did: that my mind works like that too. The constant spinning and digressing and organizing seemed so genuine. I identified with the struggle to filter experience in such a way that it at least seems to make sense, which is an ongoing, sometimes futile process.

Soderbergh, to the New York Times, 2010

Steven Soderbergh was a big Demme fan before he himself ever became a known director. According to the production diary for sex, lies, and videotape (1989), he watched Demme’s Married to the Mob (1988)3I’m sorry, this compulsive-parentheses tic is just one of those eternal in-jokes I share with myself, and it is now the official house style of Soderblog Dot Blog. My hands are tied. twice while shooting principal photography, and after they wrapped, he “borrowed David Foil’s copy of Swimming to Cambodia to watch in the editing room” for “inspiration or just a plain old break.”4The Demme entries are August 21 and September 4, 1988, respectively.

Soderbergh was interested in other people who surrounded Gray, too: he cast Ron Vawter in the role of Ann’s therapist in sex, lies, and videotape (1989), and both Vawter and Gray were founding members of the Wooster Group, a renowned experimental theater company and the incubator for Gray’s first monologues.5The world of avant-garde performance in Manhattan in the 70s and 80s was one of those miniature hotbeds in art history. Actor Willem Dafoe was another founding member of the Wooster Group, for instance, and David Byrne (of the Talking Heads) and artist Laurie Anderson were part of the same scene, leading to Demme shooting Stop Making Sense (1984) and to Anderson scoring both Swimming to Cambodia (1987) and Monster in a Box (1992). Anderson would go on to marry Lou Reed, whose bandmate John Cale had scored three of Demme’s films, including his first feature, Caged Heat (1974). And in Sex and Death to the Age 14, Gray’s first monologue, he recounts going on a “date” with playwright and director Sam Shepard—to play pool with Lou Reed. And as should be clear by now, he was a fan of Gray’s in his own right before the two ever met. It was after reading Gray’s novel,6The writing of which was the subject of Gray’s second filmed monologue, the aforementioned Monster in a Box (1992), directed by Nick Broomfield. Impossible Vacation—which was drawn from the author’s own reaction to the suicide of his mother—that Soderbergh offered Gray the part of Mr. Mungo, who dies by his own hand, in his fourth feature, King of the Hill (1993). Gray, who had dealt with suicidal ideation for years, was intrigued by the idea.

Here was a chance, I thought, to work out this fantasy in a creative way with a good director.

Spalding Gray, And Everything Is Going Fine (2010), 50:24

The sad fact is that Gray would eventually take his own life in 2004, at the age of 63. He had been suffering from the effects of a fractured skull inflicted in a car collision in Ireland in 2001, which also broke his hip, leaving him on crutches even after a long and difficult recovery. These injuries only compounded with the eye condition that inspired Gray’s Anatomy (1996). All of the above make this clip from Swimming to Cambodia (1987) seem, to me, pretty eerie.

I said earlier that the most public parts of Gray’s career exist in the shadow of this film,7Swimming to Cambodia (1987) is unfortunately quite hard to find these days—it’s not available for streaming or digital rental anywhere, at least for residents of the US, I think because it uses clips from The Killing Fields (1984) and the rights issues must be a headache. If you are not blessed enough to live within range of my beloved Movie Madness in Portland, you may have to do as I did, and get it from Netflix’s DVDs-by-mail service. (Yes, they still do those, with a superior and much more extensive inventory than their streaming catalog.) and I hope it’s clear from this clip that I meant it. Indeed, the first creative choice Soderbergh had to make after committing to shoot Gray’s Anatomy (1996) was about how he could formally distinguish a third movie about the same man sitting at a table from its predecessors.8Here’s a contemporaneous positive review of that movie, with a quick summary, from Variety; there’s also a less favorable review from what was once the San Francisco Chronicle. As of this writing, one can watch it with a subscription to the Criterion Channel, and the same goes for the interview video that yields the following quote.

There had been two other films made from his monologues, and I was trying to figure out how ours would be different. And what I decided was that we wouldn’t have an audience, and we would free ourselves up to do something that was a little more elaborate, visually.

“Steven Soderbergh on GRAY’S ANATOMY,” 2012

I’ve just dumped a lot of background on you, but the point of this blog (I remind myself) is to sift through these movies and sort out their creative constraints. Removing the audience was a significant constraint; it was also explicitly reactive. I think many of the other constraints at work were reactive ones as well.

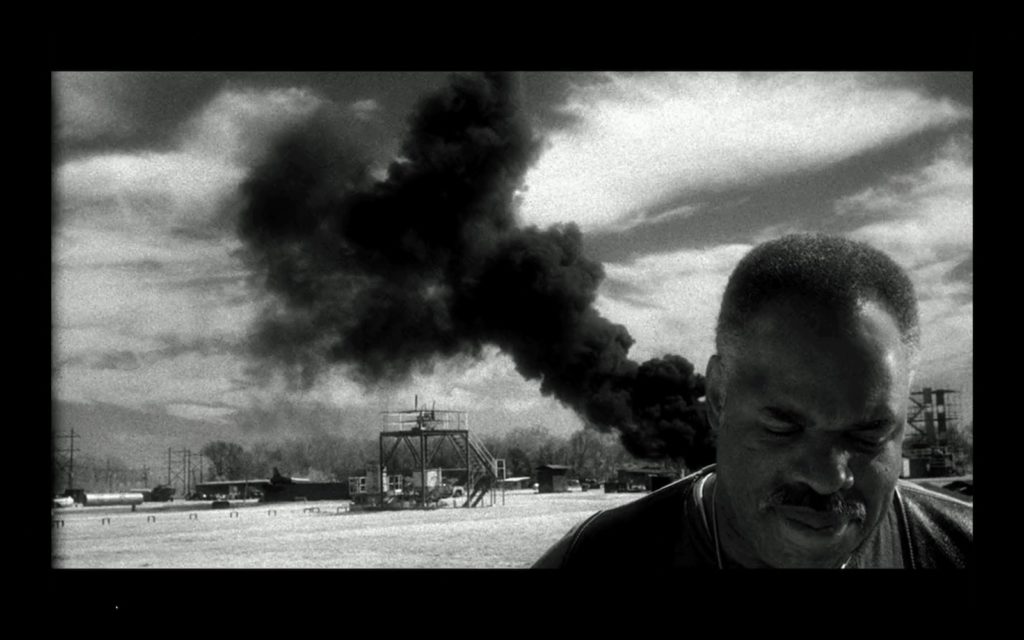

The primary story in the monologue covers Gray developing an eye condition called a macular pucker, and his subsequent approach to alternative medicine and corrective surgery. I found the subject discomfiting. Soderbergh happily provokes that further by opening the film with a series of stories from people on the street, recounting the eye injuries they suffered,9In a startling coincidence, one of these people recounts mistaking a bottle of superglue for a bottle of eyedrops—and the exact same thing happened to a webcomic artist I follow just last year. shot on infrared black-and-white film because Soderbergh claims he saw someone else try that and thought it was cool.10Per the interview quoted above—sorry all these Criterion things are paywalled—it was still film, available on hundred-foot spools that could be loaded into their movie camera only for short takes. The unexpected shifts in luminance provided by that medium dovetail with the theme of visual distortion through one’s own eyes, and make for striking images like this moment with Alvin Henry, who recounts dealing with an aneurysm in his ophthalmic artery.

The eight people who tell these stories return a few times as the movie progresses, offering their opinions on some of the alternative treatments Gray explores; they’re joined at the end by a pair of doctors who have just watched the show. The storytellers’ recurrence is doubly reactive: in Swimming to Cambodia (1987), Demme intercuts footage from Gray’s part in The Killing Fields (1984) to break up the monologue, whereas Soderbergh’s approach is to look away from Gray for a moment instead of splicing in his past self. But I discovered after watching the movie twice that the cutaways weren’t even planned for Soderbergh’s original shoot! It was only after editor Susan Littenberg completed a rough cut that it became clear that the film was well under feature length, so they went out and found new voices to expand the running time.11I haven’t been able to dig up an account of how they found these people, but I’d like to know; Gray had a practice of interviewing audience members without an agenda at some of his shows, so perhaps he was the source for them.

There is a tension between the devices of theater and those of film in Gray’s Anatomy (1996), and I think these interlocutors highlight it. While Gray’s particular method of monologue is very much an innovation of the twentieth century, the monologue is also the first form of drama we have in Western history: ancient Greek plays developed from a single actor addressing the audience, having broken away from a chorus who came to act as a foil or as interpreters. The infrared segments here stand in for that chorus, especially given the deliberate absence of a theatrical audience.

But a different kind of tension arises from that absence. Without an audience present in the recording, someone viewing the film now doesn’t get the benefit of spontaneous crowd reactions, like the laughter or gasps that must have arisen when Gray performed live. But Soderbergh wanted Gray to maintain the posture and methods of his live performance. He kept Gray seated, mostly with his customary microphone and water glass, even as each scene was shot against production design by Adele Plauché, which incorporated practical backdrop and set activity that was never part of his live staging.

When I was in college, I studied under Dr. Patrick Kagan-Moore, an extraordinary theater director, performer, and professor.12On a gamble, I emailed Patrick about Spalding Gray while working on this entry, not knowing if he had any experience with Gray; luckily for me, he did, and very kindly wrote back to provide a wealth of helpful history and context. During dress rehearsal for our production of Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane, he told the cast something I’ve never forgotten: that the product of our months of rehearsal, in which we worked out timing and inflection and intention and motivation, remained malleable, subject to change by a single live performance. “When they laugh at a line for the first time, they will train you,” he said, snapping his fingers, “like that.” It’s true! When an actor gets positive feedback from an audience, that actor will repeat it exactly the same way next time, subconsciously chasing that high.

Spalding Gray knew how to act for a camera, and he knew very well how to work with a live audience, but they are different skills and different approaches. By asking for a performance on camera that looked like the one developed in a theater, Soderbergh placed training and tools Gray developed for one medium against the surface of another. So if critical reviews like the one from the San Francisco Chronicle found Gray’s Anatomy (1996) to be self-absorbed, my hypothesis is that the missing audience provides a clue as to why.13Gray’s ex-wife and director Renee Schafransky offers another clue, which is the straightforward constraint of needing to continue working at a pace that could provide steady income. As she says in her own Criterion video about Gray, “Going to the nutritional eye doctor, going to the regular eye surgeon, going to the Philippines… all of those things—forgive me, but became more and more calculated to feed into the monologue.”

The selection of orthogonal constraints is a productive trend to follow in Soderbergh’s body of work, though, and I think it’s even more apparent in the next piece I want to discuss.

Soderbergh’s first film about Gray was a lark—a low-budget movie filmed during an eight-day break from shooting another low-budget movie,14Schizopolis (1996), which I suspect I will need a long run-up to tackle. with several cast members from the latter serving as crew on the former. His second film about Gray was a much more serious and intense project, though its crew was even smaller. It took five years to complete.

Despite the differences in scale, I’m writing about them both together here because they share more than just their central figure. In Gray’s Anatomy (1996), Gray and Soderbergh were trying to find something new at the intersection of constraints between a microbudget indie movie and a black-box one-man show. Both of those genres offer freedom from creative imposition in exchange for uncertainty about financial investment and viability, and tend to involve a long developmental period that doesn’t show up on the balance sheet. To make And Everything Is Going Fine (2010),15Here’s a contemporaneous review from NPR; the movie itself is also currently streaming on Criterion. Soderbergh and Susan Littenberg needed a very long developmental period indeed. They were even able to extend it backwards through time, in a way, by the grace of Gray’s family.

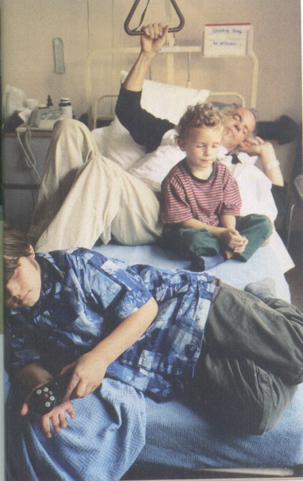

The numbers seem to vary, but a year after Gray’s death, Kathie Russo handed over either 90 or 120 hours of video—monologues, interviews, news segments, and home movies—to Soderbergh, who made a plan to develop a documentary about Gray’s life. He seems to have felt a deep sorrow and obligation toward that work.

When Kathie approached me about the documentary… I felt that there was some penance involved, because I had kind of disappeared after he was in the car accident. And it was not really rational. I had a bad feeling about it, when I heard what kind of injury it was, and I heard what was happening with him. I didn’t want to be around it. And there’s no real defense for being that bad a friend.

Soderbergh, “Making of And Everything Is Going Fine,“ 2012

I know I told you I wasn’t here to write about my personal reactions, but this one moved me. I have avoided people in my life out of my own fear, after I learned that they were struggling, and then lost them. Hesitation and reluctance have their costs.

Soderbergh’s first decision with the video archive was to hand it over to Littenberg, and to be clear, I don’t think there is any measure by which the movie is not at least much hers as his. Over a long period of work, she got it down to 15 hours of discrete story segments; from those, she and Soderbergh set a tone by selecting for the segments that made them laugh, which cut it down to six hours. Only then did the two start to try putting a shape to the film. Littenberg describes her working process as focusing on points of transition, looking for the best places to get in or out of a given piece.

Spalding was very stream-of-consciousness; he would change subjects in the middle of talking about one thing and start talking about another, so it was a real challenge.

Littenberg, “Making of AND EVERYTHING IS GOING FINE,” 2012

And if you’ll pardon my own digression, I want to talk for a moment about video games.

Patrick Holleman is a game historian, analyst, and designer, and the creator of The Game Design Forum, where he first published what would become his Reverse Design series of books dissecting titles like Chrono Trigger (1995) and Diablo II (2000). His writing is detailed, methodical, and perceptive, and the concept of working out creative constraints in retrospect is one I stole from him with relish.

Another thing I’ve taken from Holleman’s work, and which I expect to bring up many times, is his simple definition of a composite game: a work occupying two or more genres, in which the tools of one can be used to solve the problems of another.

Holleman discusses that idea with more context in his video essay about game design history and evolution.16Which also helped me understand why I am unlikely to feel again about video games the way I did in the 1990s. But that one concept alone unlocked a new perspective on genre itself for me. I find it useful now to consider it as a term meaning “a bounded creative space comprising works with significant overlap in their problems and their problem-solving tools.” I think the approach of looking for the points of intersection in a composite is valuable far outside the sphere of video games, and indeed outside interactive media.

When setting out to make And Everything Is Going Fine (2010), Soderbergh paid for the transcription of 25 years of Gray’s handwritten diaries, with the idea of using their text to fill in the narrative. Many documentaries use that kind of narrated excerpt, especially biographical documentaries, often mixed in with post-hoc interviews. But in the end, none of that text made it into the movie: if there was one thing that the filmmakers already had in ready supply, it was an expert voice narrating Spalding Gray’s life.

“I was doing a workshop with the Open Theater, which was an experimental group run by Joe Chaikin, and Joyce Aaron was running the workshop… and we were asked—and this was in 1969, in New York City—to come in and just bring in a story and jam on it, in a kind of way that if you didn’t remember the whole story, you could repeat a word. And I didn’t repeat anything once. I just did a story of my day as fast as I could speak it. And at the end of the workshop, Joyce, who was running it, asked me who wrote it. She thought it had been prewritten and memorized. And in 1969, I had a little hint that I had some sort of talent for storytelling… but there was no place for it then. And it didn’t come out until ten years later.

Spalding Gray, And Everything Is Going Fine (2010), 31:30

In developing the form he would practice for the latter half of his life, Gray and his longtime partner and collaborator Renee Schafransky addressed his dissatisfaction with the demands of writing—solitude, sustained focus on text, and silence in place of feedback—by making use of the demands—improvisation, rehearsal, and live feedback—of theater. At the same time, he was addressing his frustration with the “big machine” of the acting industry by making use of the writer-director’s power to simply cast himself as himself.17As Dr. Kagan-Moore thoughtfully pointed out to me, the last two decades have seen a number of other people—mostly men—sit down at a table with a microphone, stare into a camera, and perform a kind of “journalism” that can only be framed in quotation marks. I detest those men and their corrosive intent and effect, but if nothing else, I acknowledge that they have learned how to make their personal insecurities feel universal to their audience, in a far less honest way. I doubt they would ever credit Gray for pioneering their form; I think the lineage is still present. Very few people get to choose how the tools they develop are put to use. The tools of one became solutions to the problems of the other.

Soderbergh and Littenberg had problems to solve too. How do you make a biopic about your late friend without verging on hagiography? They way they found was to use the tools of monologue, and let him tell the story himself. How do you construct a new monologue without using your own voice? You can use the tools of montage to build meaning by way of juxtaposition. And how do you know which pieces to cut together? You sift out your subject’s sense of humor from decades of work, and then use his jokes to punctuate the arc of a biopic.

I made a chronology of his life because I really wanted to know it in my head, and then I put the monologues that he had created that pertained to each part of his life in that timeline.

Littenberg, “Making of AND EVERYTHING IS GOING FINE,” 2012

And Everything Is Going Fine (2010) runs ninety minutes, the length of most of Gray’s staged monologues, with Gray posthumously telling the story of his own life and art. Instead of using an ersatz chorus, the filmmakers bring together many different audiences from across decades, and make space and time for their reactions, placing themselves squarely in the crowd next to the viewer. There is no voiceover or new footage, but there is a full new narrative composited from pieces of the old.

Put together, those constraints on the work are quite strong, and the duration of the project reflects their challenge. But the strong constraints produced–at least by the consensus of critics and Gray’s family—strong work.

It’s interesting that at a time when we are used to being inundated with… provocative or shocking imagery, whether it’s violent or sexual, that somebody can put a string of words together that will make your knees buckle.

“Steven Soderbergh on GRAY’S ANATOMY,” 2012

A month ago I’d never seen a Spalding Gray monologue, and I certainly haven’t become an expert in the intervening time. But I think I might be at least a minor fan now, and I’d like to continue following the thread of his work with Soderbergh a little further. I’m also curious to see how Soderbergh, in the time he spent working as his own screenwriter, dealt with the constraints of adapting a novel. See you next time for King of the Hill (1993).

- 1You may wish to know, before viewing the following, that both men were fond of invoking stereotypes about Jewish women when discussing the wives they would later divorce.

- 2Who, by funny coincidence, shares the pronunciation if not the spelling of his name with John Mullany, the villain of sex, lies, and videotape (1989).

- 3I’m sorry, this compulsive-parentheses tic is just one of those eternal in-jokes I share with myself, and it is now the official house style of Soderblog Dot Blog. My hands are tied.

- 4The Demme entries are August 21 and September 4, 1988, respectively.

- 5The world of avant-garde performance in Manhattan in the 70s and 80s was one of those miniature hotbeds in art history. Actor Willem Dafoe was another founding member of the Wooster Group, for instance, and David Byrne (of the Talking Heads) and artist Laurie Anderson were part of the same scene, leading to Demme shooting Stop Making Sense (1984) and to Anderson scoring both Swimming to Cambodia (1987) and Monster in a Box (1992). Anderson would go on to marry Lou Reed, whose bandmate John Cale had scored three of Demme’s films, including his first feature, Caged Heat (1974). And in Sex and Death to the Age 14, Gray’s first monologue, he recounts going on a “date” with playwright and director Sam Shepard—to play pool with Lou Reed.

- 6The writing of which was the subject of Gray’s second filmed monologue, the aforementioned Monster in a Box (1992), directed by Nick Broomfield.

- 7Swimming to Cambodia (1987) is unfortunately quite hard to find these days—it’s not available for streaming or digital rental anywhere, at least for residents of the US, I think because it uses clips from The Killing Fields (1984) and the rights issues must be a headache. If you are not blessed enough to live within range of my beloved Movie Madness in Portland, you may have to do as I did, and get it from Netflix’s DVDs-by-mail service. (Yes, they still do those, with a superior and much more extensive inventory than their streaming catalog.)

- 8Here’s a contemporaneous positive review of that movie, with a quick summary, from Variety; there’s also a less favorable review from what was once the San Francisco Chronicle.

- 9In a startling coincidence, one of these people recounts mistaking a bottle of superglue for a bottle of eyedrops—and the exact same thing happened to a webcomic artist I follow just last year.

- 10Per the interview quoted above—sorry all these Criterion things are paywalled—it was still film, available on hundred-foot spools that could be loaded into their movie camera only for short takes.

- 11I haven’t been able to dig up an account of how they found these people, but I’d like to know; Gray had a practice of interviewing audience members without an agenda at some of his shows, so perhaps he was the source for them.

- 12On a gamble, I emailed Patrick about Spalding Gray while working on this entry, not knowing if he had any experience with Gray; luckily for me, he did, and very kindly wrote back to provide a wealth of helpful history and context.

- 13Gray’s ex-wife and director Renee Schafransky offers another clue, which is the straightforward constraint of needing to continue working at a pace that could provide steady income. As she says in her own Criterion video about Gray, “Going to the nutritional eye doctor, going to the regular eye surgeon, going to the Philippines… all of those things—forgive me, but became more and more calculated to feed into the monologue.”

- 14Schizopolis (1996), which I suspect I will need a long run-up to tackle.

- 15Here’s a contemporaneous review from NPR; the movie itself is also currently streaming on Criterion.

- 16Which also helped me understand why I am unlikely to feel again about video games the way I did in the 1990s.

- 17As Dr. Kagan-Moore thoughtfully pointed out to me, the last two decades have seen a number of other people—mostly men—sit down at a table with a microphone, stare into a camera, and perform a kind of “journalism” that can only be framed in quotation marks. I detest those men and their corrosive intent and effect, but if nothing else, I acknowledge that they have learned how to make their personal insecurities feel universal to their audience, in a far less honest way. I doubt they would ever credit Gray for pioneering their form; I think the lineage is still present. Very few people get to choose how the tools they develop are put to use.